Thursday, August 7, 2008

Keeping the Mexicutioner Closing

But, here's my hang up: If it ain't broke, don't fix it (at least, not in the middle of the season).

Case in point: Joba Chamberlain was tearing up the league as the set up man for arguably the best closer of time and all eternity, Mariano Rivera (I overheard my cousin's eldest predicting that Joba's number will eventually be retired and on display at Monument Park at Yankee Stadium). Mid-season, the Yankees decided to move Joba to the starting rotation. So, as is the accepted process, his outings gradually lengthened until his stamina and pitch-counts were up to starting levels. And, by all accounts, the kid continued to show that he could mow-down opponents, posting numbers like 3 wins, 1 loss, and a 2.76 ERA since becoming a starter.

But as impressive as the numbers are, they're less impressive if Joba can't lift his golden right arm over his head because of rotator cuff tendinitis. The Yankees had to place him on the DL recently because of this new development. And, though this seems to follow a pattern (not one that I've researched, just something that I think I've noticed) of Yankees pitchers being placed on the disabled list mid-summer and returning fresh, just in time for the playoffs, you've got to believe that they would rather have a healthy Joba starting every fifth day as they try to catch both the Red Sox and the Rays.

I've pitched enough to know the cause of rotator cuff injuries, and it almost always comes down to being overworked. Had Joba stayed in the bullpen for the remainder of this season, I seriously doubt he would have had this set-back. And, what really sucks about rotator cuff injuries is that only time (and a lot of ibuprofen) can heal them.

I was having a hard time thinking of guys that had transitioned from closer to starter. Loads of players have gone the opposite direction. One name that came to me was Rick Dempster, of the Chicago Cubs. He had been the closer for the past few seasons, saving 87 games. But, since starting didn't work out so well for Kerry Wood, he went to the bullpen, allowing Dempster to move back to the rotation. The difference between Dempster and Joba is time. Dempster had four months in the off-season and Spring Training to re-condition himself for starting pitching, while Joba's transition occurred mid-season, and with considerable pressure from fans and media.

So, here's my point: If Soria is to become a starter, it had better happen during this off-season. I'll admit, a starting rotation of Zach Greinke, Gil Meche, and the Mexicutioner (and, of course, an off-season signing of free-agent C.C. Sabathia, as long as I'm dreaming) makes me salivate like I'm sitting in front of a piping-hot deep dish pizza from Edwardo's. But, for that to happen, the Royals need to find a suitable replacement at closer (preferably one with another awesome nickname).

However, have you been to a close game at Kauffman Stadium recently (probably not)? It is exhilarating to hear "Welcome to the Jungle" blaring and to see Soria trotting in from the bullpen to get the final three outs. You know the game is over.

Like I said, I get the whole starter vs. closer debate thing. But, let's face it... right now I'm pitching as much and as well as "The Great Joba" (and for a lot less money...). Besides, it's just so sweeeeeet having a lock-down closer. I just don't want to go back to hoping our guy can hold the lead and get the save. So for now, let's just be grateful that the Mexicutioner is healthy and still, well, mexicuting.

Friday, July 11, 2008

Anthing Better?

Tonight is another promotional night. I guess this weekend they're giving away hats at the games on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Tonight it's straw cowboy hats. Tomorrow it's "Christmas in July" for some reason, and they're giving out Santa hats (just what I always wanted - a furry, red Santa hat in Kansas City in the dead-heat of summer). But because the cowboy hats aren't too bad, and because we'll be going to the Days of '47 Rodeo in Salt Lake City in less than two weeks, we're making our way out to Kauffman Stadium early tonight.

Is there anything better than being in your seats 90 minutes prior to the first pitch? I love it when I'm able to watch the visitors take batting practice. I usually have no idea who's hitting, but I don't really care. For me it's not about watching a Major League slugger like Manny Ramirez hit lazers off the wall during bp. It more like an insight to the game. A backstage pass to be able to seen the inner-workings of a professional baseball team. The next time you're at a ball game early enough to see batting practice, pay close attention and you'll notice all sorts of things going on, not just the starting nine getting their swings in before the game.

You might notice a couple of coaches hitting ground balls to some infielders between pitches, who then throw the ball back across the field to another player at first base, who is protected by a large square screen. The screen at first base is usually one of three screens out on the field. There is another square screen that is just behind second base in shallow centerfield that protects the man with the bucket. When the other players in the field shag the balls being hit by the man at the plate, they throw them in to the player with the bucket. Eventually, the coach who is throwing batting practice (pitching), who is protected by the third screen, the "L-screen," will run out of baseballs, and the bucket is called for to replenish the supply.

Besides batting practice I love to see the starting pitchers go through their routines before the game. It usually starts after batting practice, but you might see them stretching before the visiting team is done. Every pitcher is different, but usually they'll start with a little jog to get the blood going, followed by some stretching, then some throwing. They'll often start close, but by the time they're ready to go to the mound they've usually stretched their throws nearly the entire way from the foul line to the center field fence. After they bring it back in, it's time to head to the bullpen with the starting catcher. Seeing a pitcher throw in the bullpen makes it look so effortless and easy. He might just be throwing 75-80%, saving the good stuff for the game, but some pitchers might cut it loose a few times just to see how the old arm feels that night. This entire ritual can take as long as 45 minutes, so check the clock to see how early the starting pitchers are loosening up for the game the next time you're at the ballpark early.

Another reason to get there early is to watch the magic of the grounds crew. This is an entire post in itself, one that I'm going to do soon, so I'll only say this: the field looks good when you get there, but by the time the crew is done marking the foul lines and the batters box, raking the mound and the infield, and replacing the bases with glowing white "gamers," the field transforms into a place of dreams.

No, there's not much better than being in your seats early at the ballpark. Especially if there's a promotional t-shirt, bobblehead, or cowboy hat involved, on top of everything else.

Friday, July 4, 2008

The Mexicutioner

Somewhere along the way a scout -- no, not a Boy Scout, a professional baseball scout -- came to Mexico to see Jack and his friends play baseball. The Scout also wanted Jack to be on his side, and, October 31, 2001, when Jack was 17 years old, he signed a free agent contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

The following season he pitched a total of five innings for the Gulf Coast League Dodgers, a Rookie-league affiliate of the team he had signed with the year before. But due to injuries, that was all Jack would pitch with the Dodgers. They released him on October 12, 2004.

But Jack continued to play with his friends in La Liga Mexicana de Beisbol (that's "The Mexican Baseball League," for all of you Gringos out there). Then, one day, more than a year after being released, another scout came to see Jack play ball. He also wanted Jack on his side, and he signed a new free agent contact with the San Diego Padres.

The next season Jack played with some new friends on the Fort Wayne Wizards, the single-A minor league affiliate of the Padres. But, Jack only played in 7 games that season, and only threw 12 innings.

Because Jack was still so young, 20 years old at that time, and because he had not thrown much for the Padres, he was not included on their 40-man roster. Jack was still considered a project that would take more time to develop, and the 40-man roster was reserved for players who were ready to play in the big leagues at any time.

But, as in all good fairy tales, there's a twist.

In Major League baseball there is a Collective Bargaining Agreement between the Players Association (the most powerful Union on Earth) and the Owners. Rule 5 of that agreement sets the parameters for an annual draft to be held during the Winter Meeting for General Managers in December. The purpose of this draft is to ensure that no club can stockpile young, talented players in their minor league teams who might otherwise have a shot to play in the big leagues if they were with a different organization. Any player that is not on a 40-man roster is eligible to be drafted by another team. However, the team that selects a player must immediately place that player on their 25-man Major League roster, and the player must remain there the entire season or else he will be sent back to his original club. This is called the Rule 5 draft.

Now back to our story...

In 2006 there was another scout who saw Jack pitch. But this scout saw something the other scouts had not seen. This scout saw something special about Jack and he definitely wanted him on his side. So, a little later that year, in December of 2006, the Kansas City Royals selected Joakim Soria in the Rule 5 draft. He had been left unprotected by the San Diego Padres (and who can blame them, really), so the Royals decided he was worth a shot.

Then, December 9, 2006, just two days later, while Jack was playing with his friends in Mexico, he pitched a perfect game. 27 men came to the plate that day, and 27 men made their way back to the dugout, unsuccessful at reaching first base.

The Royals were glad to have Jack on their side, but he was only 22 years old when the 2007 season began, so they understood that he might still need some time before he would be competitive at the Major League level. But, according to the rules of the Rule 5 draft, the Royals had to keep Jack on the Major League team for the entire season before being able to option him to the minor leagues for further development. So, that year, Jack was going to be pitching out of the bullpen.

On April 4, 2007, the Royals were losing 1-7 against the Red Sox. The game was all but out of hand, so they decided to give Jack a chance to pitch in the Major Leagues. In his debut, he pitched two-thirds of an inning and allowed no runs and no hits, walking one batter. He pitched pretty well in his first time out. But Jack would continue to pitch well. In the next week, he would pitch 5 1/3 innings in four games and allowed no runs, only one hit and one walk while striking out six men and earning his first Major League save on April 10th against the Toronto Blue Jays. He finished the season with 17 saves, 19 BB, 75 SO, with an ERA of 2.48. Not bad for a guy with fewer than 20 innings pitched in the minor leagues.

This season, Jack has been even better. He earned his 23rd save last night (his 23rd in 24 tries), while striking out 41 in 35 innings of work. Jack is now one of the best closers in the game today. The Royals recently signed him to a big contract extension worth a lot of money. Joakim the Dream is living it. He now has many nicknames: Cap'n Jack, Joakim No-Scoria and the Emancipator (because of his sweet Abe-Lincoln beard) just to name a few. But the one that best describes his emotionless efficiency is his new-found title -- the title of The Mexicutioner. Royals fans everywhere -- Jack's new friends -- are overjoyed now that he's on their side.

Saturday, June 21, 2008

Amphibious Pitcher

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Thanks A Lot, Chien-Ming

Prior to my senior year of high school, I played outfield and pitched. When I was 15 years old I also played some third base and even a little shortstop, depending on who was pitching on a given night. I was never a great hitter, but I was pretty good. I had what they call "warning track power." I was good for a nice double in the gap to the wall, but I have exactly one career home run. It was a game-winner in a JV game my junior year of high school. I was more of a line drive guy... That's my story, and I'm sticking to it.

Prior to my senior year of high school, I played outfield and pitched. When I was 15 years old I also played some third base and even a little shortstop, depending on who was pitching on a given night. I was never a great hitter, but I was pretty good. I had what they call "warning track power." I was good for a nice double in the gap to the wall, but I have exactly one career home run. It was a game-winner in a JV game my junior year of high school. I was more of a line drive guy... That's my story, and I'm sticking to it.I also played some basketball in high school until the coach decided he didn't like baseball players. Truly, he didn't like that baseball players spent their summers playing in tournaments all over the country instead at his little basketball summer camps, but I digress.

My senior year in high school was the year that I became primarily a pitcher. And, no matter what I had done or been in the past, it was also the year I became a non-athlete. Because, as everyone knows, pitchers aren't athletes. Except for, well, I didn't believe it, and I spent the rest of my time in the game trying to prove that I was an athlete, I just happened to pitch better than I hit.

One of the greatest compliments I ever received was kind of an insult. I was playing a little pick-up basketball with some other missionaries one day. After a few games, one said to me, "Geez, Reynolds. You're pretty good. I wouldn't have thought you were athletic at all." By that time in my life, I had put on a few pounds and added a chin. I also had my glasses on, which didn't help matters any, so I couldn't blame him.

Anyway, back to the point. Pitchers get a bad wrap for being non-athletes. Sure, sometimes they look a little goofy covering first base and handling the toss from the first baseman. Occasionally they launch a perfect double-play ball over the shortstop's head and into center field. But overall, pitchers are every bit the athletes as the position players. They just specialize in different things.

But just when you think you might have people convinced, Chien-Ming Wang pulls up lame while running the bases. No, he didn't twist his ankle sliding safely into third base on a close play. It happened when he scored from second base on a base hit to right field. There wasn't even a throw to the plate when he scored. According to the Yankees' web site, he was diagnosed with a "mid-foot sprain of the Lisfranc ligament of the right foot and a partial tear of the peroneal longus tendon of the right foot."

I know what you're thinking, and yes, I'm serious. He did all of that rounding third base and scoring. And, making the situation even more ridiculous, the new Steinbrenner in charge of the Yankees got his panties in a bunch because the National League doesn't use the DH (Designated Hitter). And, since his team was playing an Interleague match-up on the road, his front-line starter had to --gasp-- run the bases.

Hank Steinbrenner might think it was the National League's fault, but maybe this whole thing could have been avoided if only Wang would have had some better arch-supports in his cleats. That, or maybe one of the athletes on the team should have given him some baserunning pointers. Then again, did anyone really expect him to even get on base in the first place? After all, he is just a pitcher, right?

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Starters Can't Win Without Closers

He has been so good that there has been much debate as to whether the Royals might be better served with him in the starting rotation instead of anchoring the bullpen. So, which is more important, a good starter, or a good closer?

Stat geeks will tell you that there's not much to debate here. A good starter can provide 200 quality innings per season, whereas an elite closer on a good team might only be used in about 70 games. Therefore, there is much more "value" in a starter than a closer.

But I'm not a stat geek, so I don't see things in black and white. I've played the game and I both appreciate and respect the human element, even if it is difficult to quantify.

Let's look at the case of the Atlanta Braves. The Braves won their division an incredible 14 straight seasons (the next highest division winning streak in history is owned by the Yankees with eight). That is 14 consecutive trips to the playoffs. Do you know how many times they won the World Series? Once. One big reason for this was their closer, Mark Wohlers, was at the top of his game that postseason. They had virtually the same starting rotation for a majority of their postseason run including three future hall of famers: Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz.

Prior to the appearance of El Matador, Joakim "When I pitch, you no Scoria," the Royals had some dismal options at closer. When we moved to Kansas City in 2006, I attended a handful of games towards the end of the season. No lead was safe. Ambiorix Burgos blew a franchise record number of saves that year. He threw really, really hard. Problem was, he couldn't pitch. Then, in the off-season, the Royals picked up a kid from Mexico for a song from the San Diego Padres. A week later, he threw a perfect game in a Mexican Winter League. Before the end of the 2007 season, Soria was the closer, and was doing a great job. The bullpen, which had been a major weakness, had become one of the Royals' strongest assets.

Because the Royals are, well, the Royals, and their offense can struggle to put runs on the board, a lock-down closer is much more important than a starter. Some of the recent Red Sox lineups could afford to close by committee because they could out-hit and out-score most opponents.

Moving Joba Chamberlain to the starting rotation is probably a good idea for the New York Yankees. Their starters are having some trouble and they already have an amazing closer. But moving Soria to the rotation this season is probably not a good idea. Their starters have been good. It's most likely the best starting rotation they've had in years. And, if Soria starts, who is going to close? They have some good pitchers in the bullpen, but right now, they have a bonafide closer who can be counted on to finish games. Closing out games takes a different kind of mentality, and not everyone can do it, no matter how good a pitcher is.

Top-shelf starters are great. But even the best pitchers have to eventually turn the game over to the bullpen. If there's no one to close out the game and preserve the lead, an ace could rack up a load of no-decisions that shoulda, coulda, woulda been wins.

True aces are tough to come by. If you knew for sure that Soria would be an ace, then you should probably find someone to replace him as closer and start the transition. However, there's an old saying that goes something like this: If it ain't broke, don't fix it. For now he's found a niche and he's more important to the club in his current role. But who knows what the future holds?

Wednesday, April 2, 2008

Beating the System: Brian Bannister

Growing up, I wasn't what you would call the star of my teams. There's only one team I have ever been on where I could maybe, possibly say that I was the best player, and that was a really bad team. I started pitching when I was 9 years old. I wanted to pitch when I was eight, but only one eight year old pitched on that team, and it wasn't me. It was an eight year old who looked twelve, who my eleven year old self feared three years later whenever I knew he would be pitching against me, and with whom my fourteen year old self was glad be teammates again. He, for the greater part of our youth, was the fireballer on the mound who no one wanted to face. I, from the time I was fourteen all the way through college, was the unimposing, right-handed, "other" pitcher who opposing teams were happy to draw, thinking they had caught a break.

Growing up, I wasn't what you would call the star of my teams. There's only one team I have ever been on where I could maybe, possibly say that I was the best player, and that was a really bad team. I started pitching when I was 9 years old. I wanted to pitch when I was eight, but only one eight year old pitched on that team, and it wasn't me. It was an eight year old who looked twelve, who my eleven year old self feared three years later whenever I knew he would be pitching against me, and with whom my fourteen year old self was glad be teammates again. He, for the greater part of our youth, was the fireballer on the mound who no one wanted to face. I, from the time I was fourteen all the way through college, was the unimposing, right-handed, "other" pitcher who opposing teams were happy to draw, thinking they had caught a break.They hadn't, but thinking they had probably played right into my hands. There really wasn't anything too impressive about me as pitcher. I didn't throw hard, that's for sure. But velocity is only one of the components to being a successful pitcher. It's practically universally accepted that there are four altogether, and here they are, in no particular order: Velocity (how hard the ball is thrown), Location (throwing it where you want to throw it), Movement, (making it curve, slide, cut, sink, split, knuckle, or explode), and Changing Speeds (throwing some hard and some harder). Coaches and scouts always said that none of those four aspects of pitching was more important than the others. Guys like me though, know the truth. When they come up a hand-held device for scouts that measures anything other than velocity, let me know. People would always say that I didn't throw hard enough to be effective and I spent most of my time proving them wrong. And that brings me to Brian Bannister.

Brian Bannister is a pitcher for the Kansas City Royals. Last year, in his rookie season, he put up numbers that placed him in contention for the American League Rookie of the Year. His Earned Run Average (ERA) was 3.87. He won 12 games (which no Royals pitcher had done in five years). And he did it with less than average Major League stuff. Even Bannister himself admits, "I know I’m just a guy with average ability. I’m trying to pitch in the major leagues, against the best hitters in the world. I’m pitching against guys who are like 7 feet tall and can throw 98 mph and have sliders that explode. I mean, seriously, look at me. What am I doing here?"

What is he doing here? Multiple sources say that he is wicked smart. He received a perfect score on the math section of his SAT, and graduated cum laude from USC. And that is why I love this guy. Too often you see pitchers that can throw the ball through a barn wall, provided they can actually hit its broad side -- guys with "million-dollar arms and ten-cent noggins," to borrow a phrase I read somewhere. Not Bannister. He knows who he is, and he's smart enough, and has studied enough to know who he's facing, probably better than they know themselves.

Despite his staggering intellect and his promising rookie season, the geeks (and I say geeks in the most endearing sense of the word) behind Baseball Prospectus have projected that Bannister will have quite the sophomore slump this year with an ERA of 5.19, and a 6-8 win-loss record. They attribute this to his freakishly low BABIP (batting average of balls in play) of .264 from a season ago. The League average is .303, so with a less than stellar walk to strikeout ratio, Baseball Prospectus basically thinks his luck will run out this season. Bannister disagrees, and he's aiming to prove them wrong.

This afternoon was the chance he had to do so, and just like any other test he's ever taken, he flew through this one with near-perfect results. Going head to head with Detroit's potent offense, you might figure it to be a long afternoon for this pitcher who looks more like a guy who should be crunching numbers at a desk than punching out Major Leaguers, but not today. Bannister threw seven innings, striking out four, walking none, allowing no runs, and only three hits. His current ERA of 0.00, and record of 1-0 seem like the perfect start to a season in which Brian Bannister takes on the stat men and wins.

Thursday, March 27, 2008

Revisiting the Knuckleball

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

The Dance of the Knuckleball

Watching a little of Game 4 of the American League Championship Series (ALCS) last night at a friend's house, I was able to see Tim Wakefield pitch for the Boston Red Sox. Unfortunately, he wasn't doing so well when we tuned in, so he didn't stay on the mound for long. But, seeing him pitch and seeing the frustration of many of the Indians' hitters made me think about the Knuckleball. Having pitched myself, I know how difficult it is to throw a knuckleball and how it is even harder to catch, much less hit. Many times the action on a knuckleball is described as dancing, fluttering, or dipping and diving. It is difficult to get a real sense of just how much movement is on that pitch if you're just watching the game on television. But trust me, I've played catch with an outfielder in college who could throw a good knuckler, and I was always worried that I would miss it and it would hit me in the face.

With most pitches, pitchers are trying to increase the amount of spin on the ball, as well as the direction. But with a knuckle, the pitcher is actually trying to minimize the amount of spin on the ball. By decreasing or eliminating the spin on the ball, the movement of the pitch becomes random and somewhat unpredictable. If you've ever played volleyball at a family picnic, you may have experienced a knuckleball effect. When a volleyball is served with little or no spin, the seams of the ball as well as the ridges and valleys of the ball causes it to "float," or to knuckleball.

Here's a good connection to a past posting: In the recent post about baseball movies I talked about "Eight Men Out," a story of the 1919 Chicago White Sox and how they were bought off in exchange for throwing the World Series. One of the pitchers, Eddie Cicotte, is widely credited as the first knuckleball pitcher, and finished his career with 221 wins. Some say he may have been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame had he not been (spoiler alert) banned from baseball for his involvement in the Black Sox scandal.

Here's a good connection to a past posting: In the recent post about baseball movies I talked about "Eight Men Out," a story of the 1919 Chicago White Sox and how they were bought off in exchange for throwing the World Series. One of the pitchers, Eddie Cicotte, is widely credited as the first knuckleball pitcher, and finished his career with 221 wins. Some say he may have been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame had he not been (spoiler alert) banned from baseball for his involvement in the Black Sox scandal.So, would you like to learn how to throw a knuckleball? Me too. I could actually explain how to throw it, but I can't really do it myself (Actually, there are quite a few things about baseball that I could explain mechanically, but I can't actually do well... Maybe coaching is in my future). But I found this video tutorial to help you learn. Notice the sudden movement of the ball back to your right just before the ball crosses the plate.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Radar Guns in Baseball

About a month ago I read an article in the Sports section of the Kansas City Star. I would have posted a link to it, but it has been "archived," so I would have to pay for it; and since no one likes to click on the advertisements on the left, I'm not making a dime on this blog. It was written by Joe Posnanski, recently voted the best sports writer in America. I've always enjoyed his stuff, but this particular article held special meaning for me. It was entitled, "You Can't Always Judge a Pitcher by His Fastball" -- Amen.

There were two questions that he addressed in his article: First, what has been the impact of the radar gun in baseball, and second, is Rowdy Hardy a real, bonified prospect for the Kansas City Royals. As it turns out, it was pretty much the same question, just stated differently.

Rowdy Hardy is currently pitching in A-Ball for the Royals' organization, and pitching well. His numbers rival any pitcher in the minor leagues. 14-4 on the season, 84 strikeouts, and only 14 walks. His ERA (Earned Run Average) is well under 3.00. But the numbers that keep him in Single-A are 81-82 -- which is about how hard he throws his fastball. If he threw 91-92, with the same numbers, the Royals wouldn't be able to move him up fast enough. As it sits, however, they're not exactly sure what they have in Hardy. Dayton Moore, the General Manager for the Royals, has said that next year he will play on the Double A squad, and that he will continue to move up in the organization until guys start to hit him.

Earl Weaver helped to pioneer the use of the radar gun in baseball. A legendary, hall of fame manager for the Baltimore Orioles, Weaver was obsessed with statistics and information. His purpose for using the radar gun wasn't to see how hard guys were throwing, but to better judge the difference between his pitchers' fastballs and off-speed pitches. For example, if a guy throws a fastball at 85 mph and his change-up comes in at 80 mph, it's really just a fat fastball, and he won't fool anyone with it. But, if someone was throwing their fastball 85 mph and the change-up at 69 mph, that was something they could work with and get guys out with. Weaver understood that pitching is much more than just how hard you can throw. The trick to pitching well is to keep the batter off balance, and you can do that by changing speeds and location. If a batter knows you throw a curveball that loops in there at about 65-67 mph, and your change-up looks just like your fastball, but it makes its way to the plate at about 70 mph, it makes your 80-81 mph fastball seem that much "quicker" to the plate. It's like Einstein said -- it's all relative.

So, while it is not necessary to throw the major league average 91-92 mph, it really is. Radar guns have changed the way scouts evaluate pitching prospects, and in most cases, unless a guy has a good, major league fastball, they could care less about any other abilities you may possess. But, every now and then a little left-hander like Rowdy Hardy takes their formula and throws it out the window -- at a blazing 82 mph.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

A Perfect Game

There are many feats for which a pitcher strives. A complete game, for example is when a single pitcher is able to throw each inning of the game. This doesn't happen as much as it did in the old days, before the baseball world became obsessed with pitch counts. Now, to throw a complete game, a pitcher not only needs to get guys out, but do it efficiently with as few pitches as possible. Additionally, the prevalence of dominant (or at least, hard-throwing) closers who usually come into a game in the ninth inning to get the final three outs, and the likelihood of throwing a complete game diminishes even more. On top of that, if there's an ace on the mound, throwing really well, keeping his pitch count down, but his team is ahead by so many runs that the opposing team has no real chance of winning, the ace will usually be rested and the manager will call upon the bullpen in 8th inning or so. Yeah, complete games are not as common as they used to be.

There are many feats for which a pitcher strives. A complete game, for example is when a single pitcher is able to throw each inning of the game. This doesn't happen as much as it did in the old days, before the baseball world became obsessed with pitch counts. Now, to throw a complete game, a pitcher not only needs to get guys out, but do it efficiently with as few pitches as possible. Additionally, the prevalence of dominant (or at least, hard-throwing) closers who usually come into a game in the ninth inning to get the final three outs, and the likelihood of throwing a complete game diminishes even more. On top of that, if there's an ace on the mound, throwing really well, keeping his pitch count down, but his team is ahead by so many runs that the opposing team has no real chance of winning, the ace will usually be rested and the manager will call upon the bullpen in 8th inning or so. Yeah, complete games are not as common as they used to be.

A shutout is a pitching accomplishment which entails holding the opponents scoreless for the entire game. A shutout, unlike like a complete game, doesn't need to be thrown by just one pitcher. When it is, it is referred to as a "complete game shutout." But, just like complete games, shutouts are also hard to come by. In today's world of bigger players, harder throwers, and longer homeruns, even the Kansas City Royals, one of the most futile teams in recent history, are averaging over three runs a game, and have only been shutout once in 28 games so far. The next step up from the shutout, and holding the opponent scoreless is holding them hitless. No-hitters (a complete game without giving up a hit) are rare as well. In the history of the game, there have only been 234 no-hitters. Most no-no's (that's "baseball talk" for a no-hitter) are thrown by just one pitcher, though on rare occasion, multiple pitchers may combine for nine innings if no-hit ball. The Houston Astros, for example, set a Major League record on June 11, 2003 by sending six different pitchers to the mound at Yankee Stadium, none of whom allowed a single hit. The most recent no-hitter was thrown by White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle when he threw against the Texas Rangers April 18, 2007. It was the first no-hitter in the American League since Derek Lowe’s no-no for the Boston Red Sox in a 10-0 win against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 2002.

The next step up from the shutout, and holding the opponent scoreless is holding them hitless. No-hitters (a complete game without giving up a hit) are rare as well. In the history of the game, there have only been 234 no-hitters. Most no-no's (that's "baseball talk" for a no-hitter) are thrown by just one pitcher, though on rare occasion, multiple pitchers may combine for nine innings if no-hit ball. The Houston Astros, for example, set a Major League record on June 11, 2003 by sending six different pitchers to the mound at Yankee Stadium, none of whom allowed a single hit. The most recent no-hitter was thrown by White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle when he threw against the Texas Rangers April 18, 2007. It was the first no-hitter in the American League since Derek Lowe’s no-no for the Boston Red Sox in a 10-0 win against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 2002.

Simply put, a perfect game is a complete game in which no opposing player ever reaches base safely—27 up, 27 out. How rare is a perfect game? Only 17 pitchers have tossed perfect games in Major League history. If you give up a hit, it's gone, and so is your no-no by the way. As if throwing a no-hitter isn't hard enough, throw four pitches out of the strike zone to one batter, and away walks your bid for perfection. If your sinker runs too far inside and hits a batter, you're not perfect enough. Literally, no one must reach base—not even on an error by the young shortstop that was just called up from AAA. If you're lucky enough to be perfect on the mound, it is something you will never forget, nor will anyone in attendance that day.

A perfect game is one of those achievements that have the ability to immortalize an athlete. It is as rare as a hole in one, maybe even more so; because unlike a hole in one, a pitcher can't get lucky one time and throw a perfect game. He must go out and pitch to the best baseball players in the world inning after inning. A pitcher relying on luck will soon find that it runs out at the most inopportune moments.

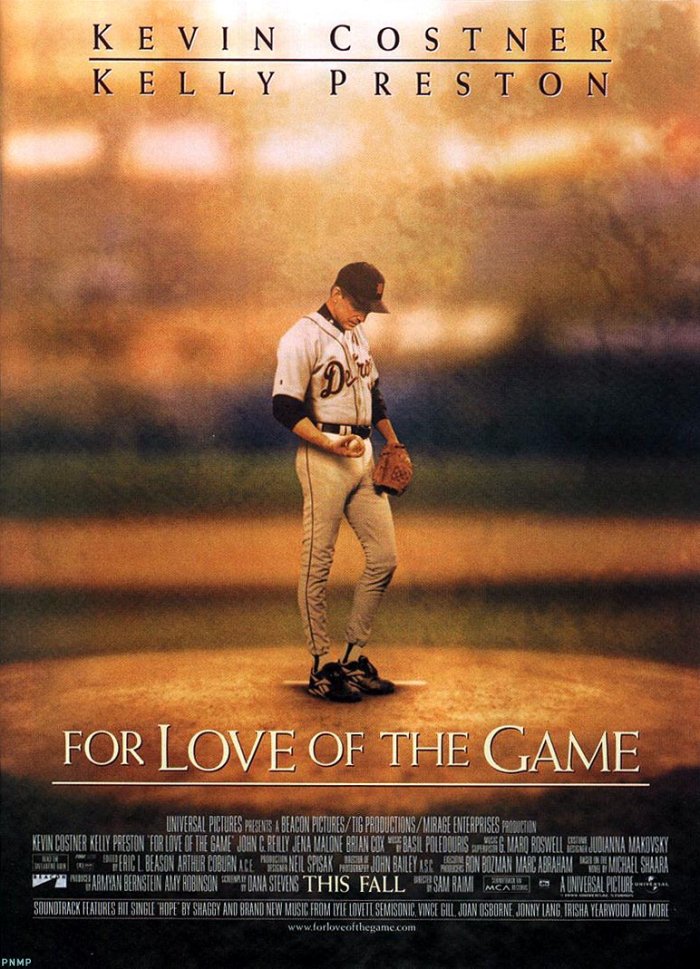

For Love of the Game (1999) is a great baseball movie that follows fictional aging ace Billy Chapel (Kevin Costner) in his quest for a perfect game on what could be the final game of his career. This show does a great job of showing all of the drama of a perfect game while reminding us that it doesn’t happen like the Randy Johnson clip of out after out. The pitcher has plenty of time to sit and think while his team bats each inning, which only adds to the difficulty of a perfect game. It also brings up one extremely important facet of a perfect game that everyone should know—don’t jinx it!

For Love of the Game (1999) is a great baseball movie that follows fictional aging ace Billy Chapel (Kevin Costner) in his quest for a perfect game on what could be the final game of his career. This show does a great job of showing all of the drama of a perfect game while reminding us that it doesn’t happen like the Randy Johnson clip of out after out. The pitcher has plenty of time to sit and think while his team bats each inning, which only adds to the difficulty of a perfect game. It also brings up one extremely important facet of a perfect game that everyone should know—don’t jinx it!