A few people have asked about my blog's name, The Perfect Game. Baseball-savvy individuals that find this blog will hopefully appreciate the name's double meaning, especially coupled with the blog's web address (http://27up27out.blogspot.com). For me, at least, Baseball

is the perfect game. There is no other sport that can captivate me as baseball can. But, perhaps I will expound on its overall perfection in a future post. For now, the topic is

a perfect game—nine innings of determination, stamina, and most times, a little luck.

There are many feats for which a pitcher strives. A complete game, for example is when a single pitcher is able to throw each inning of the game. This doesn't happen as much as it did in the old days, before the baseball world became obsessed with pitch counts. Now, to throw a complete game, a pitcher not only needs to get guys out, but do it efficiently with as few pitches as possible. Additionally, the prevalence of dominant (or at least, hard-throwing) closers who usually come into a game in the ninth inning to get the final three outs, and the likelihood of throwing a complete game diminishes even more. On top of that, if there's an ace on the mound, throwing really well, keeping his pitch count down, but his team is ahead by so many runs that the opposing team has no real chance of winning, the ace will usually be rested and the manager will call upon the bullpen in 8th inning or so. Yeah, complete games are not as common as they used to be.

There are many feats for which a pitcher strives. A complete game, for example is when a single pitcher is able to throw each inning of the game. This doesn't happen as much as it did in the old days, before the baseball world became obsessed with pitch counts. Now, to throw a complete game, a pitcher not only needs to get guys out, but do it efficiently with as few pitches as possible. Additionally, the prevalence of dominant (or at least, hard-throwing) closers who usually come into a game in the ninth inning to get the final three outs, and the likelihood of throwing a complete game diminishes even more. On top of that, if there's an ace on the mound, throwing really well, keeping his pitch count down, but his team is ahead by so many runs that the opposing team has no real chance of winning, the ace will usually be rested and the manager will call upon the bullpen in 8th inning or so. Yeah, complete games are not as common as they used to be.

A shutout is a pitching accomplishment which entails holding the opponents scoreless for the entire game. A shutout, unlike like a complete game, doesn't need to be thrown by just one pitcher. When it is, it is referred to as a "complete game shutout." But, just like complete games, shutouts are also hard to come by. In today's world of bigger players, harder throwers, and longer homeruns, even the Kansas City Royals, one of the most futile teams in recent history, are averaging over three runs a game, and have only been shutout once in 28 games so far.

The next step up from the shutout, and holding the opponent scoreless is holding them hitless. No-hitters (a complete game without giving up a hit) are rare as well. In the history of the game, there have only been 234 no-hitters. Most no-no's (that's "baseball talk" for a no-hitter) are thrown by just one pitcher, though on rare occasion, multiple pitchers may combine for nine innings if no-hit ball. The Houston Astros, for example, set a Major League record on June 11, 2003 by sending six different pitchers to the mound at Yankee Stadium, none of whom allowed a single hit. The most recent no-hitter was thrown by White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle when he threw against the Texas Rangers April 18, 2007. It was the first no-hitter in the American League since Derek Lowe’s no-no for the Boston Red Sox in a 10-0 win against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 2002.

The next step up from the shutout, and holding the opponent scoreless is holding them hitless. No-hitters (a complete game without giving up a hit) are rare as well. In the history of the game, there have only been 234 no-hitters. Most no-no's (that's "baseball talk" for a no-hitter) are thrown by just one pitcher, though on rare occasion, multiple pitchers may combine for nine innings if no-hit ball. The Houston Astros, for example, set a Major League record on June 11, 2003 by sending six different pitchers to the mound at Yankee Stadium, none of whom allowed a single hit. The most recent no-hitter was thrown by White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle when he threw against the Texas Rangers April 18, 2007. It was the first no-hitter in the American League since Derek Lowe’s no-no for the Boston Red Sox in a 10-0 win against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays in 2002.

Shutouts are sweet. Complete game shutouts are even better. A no-hitter is dream come true for any pitcher. But the perfect game is something all together magical.

Simply put, a perfect game is a complete game in which no opposing player ever reaches base safely—27 up, 27 out. How rare is a perfect game? Only 17 pitchers have tossed perfect games in Major League history. If you give up a hit, it's gone, and so is your no-no by the way. As if throwing a no-hitter isn't hard enough, throw four pitches out of the strike zone to one batter, and away walks your bid for perfection. If your sinker runs too far inside and hits a batter, you're not perfect enough. Literally, no one must reach base—not even on an error by the young shortstop that was just called up from AAA. If you're lucky enough to be perfect on the mound, it is something you will never forget, nor will anyone in attendance that day.

A perfect game is one of those achievements that have the ability to immortalize an athlete. It is as rare as a hole in one, maybe even more so; because unlike a hole in one, a pitcher can't get lucky one time and throw a perfect game. He must go out and pitch to the best baseball players in the world inning after inning. A pitcher relying on luck will soon find that it runs out at the most inopportune moments.

Another aspect of a perfect game is how important the eight other men on the field become. No one is going to strike out 27 batters, so the defense must come up with play, after play, after play. The pitcher is the player who goes down in the history books, but the credit should somehow go to the entire team. The most recent perfect game in the majors was thrown by Randy Johnson, then with the Arizona Diamondbacks, on May 18, 2004, against the Atlanta Braves. MLB.com has incredible footage of all 27 outs that day at the above link. Notice how close the first batter comes to ruining Johnson’s perfect day before anyone even imagines it could happen. If it weren’t for a tremendous play by the first baseman, the lead-off man is on base and it’s just another day at the ballpark.

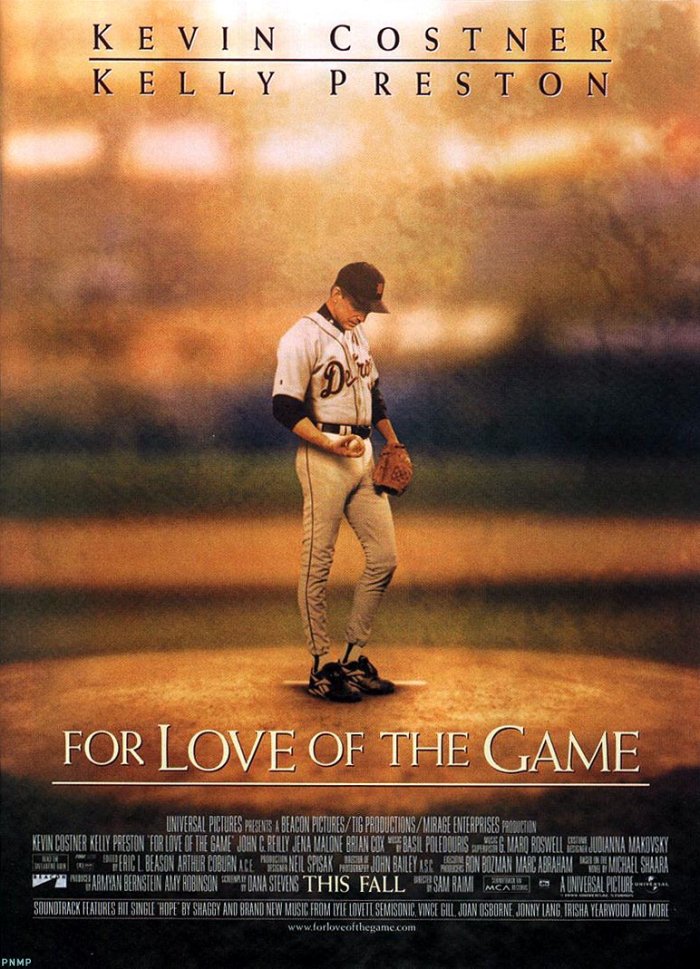

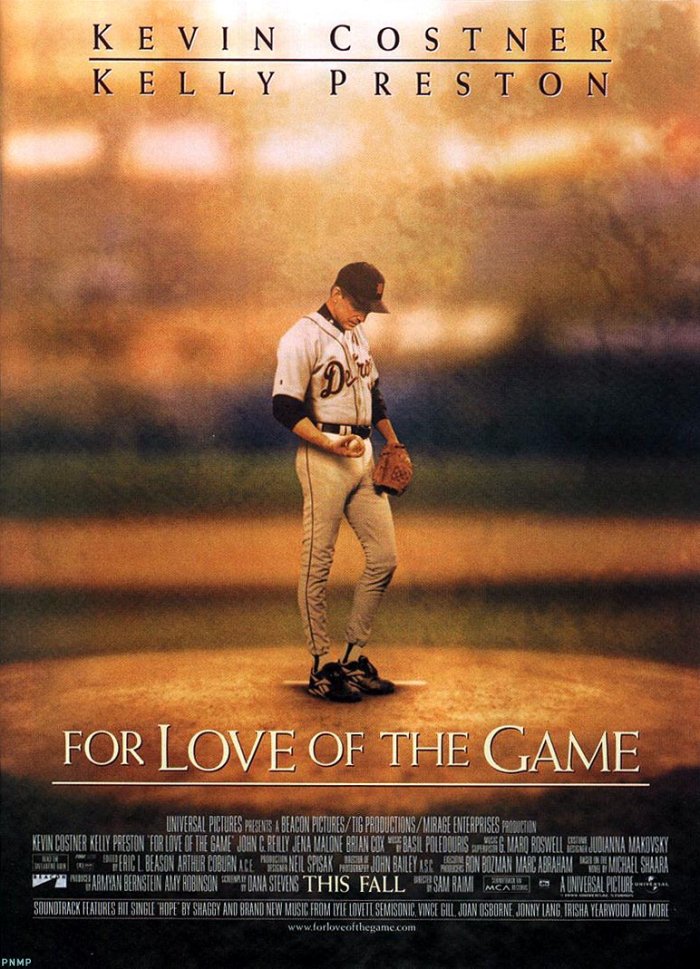

For Love of the Game (1999) is a great baseball movie that follows fictional aging ace Billy Chapel (Kevin Costner) in his quest for a perfect game on what could be the final game of his career. This show does a great job of showing all of the drama of a perfect game while reminding us that it doesn’t happen like the Randy Johnson clip of out after out. The pitcher has plenty of time to sit and think while his team bats each inning, which only adds to the difficulty of a perfect game. It also brings up one extremely important facet of a perfect game that everyone should know—don’t jinx it!

For Love of the Game (1999) is a great baseball movie that follows fictional aging ace Billy Chapel (Kevin Costner) in his quest for a perfect game on what could be the final game of his career. This show does a great job of showing all of the drama of a perfect game while reminding us that it doesn’t happen like the Randy Johnson clip of out after out. The pitcher has plenty of time to sit and think while his team bats each inning, which only adds to the difficulty of a perfect game. It also brings up one extremely important facet of a perfect game that everyone should know—don’t jinx it!

I don’t care if you’re watching a professional baseball game, a college game, a high school game, or your 8-year-old nephew’s little league game—if you suddenly realize that not only has the pitcher not given up a hit, but you can’t remember any baserunners at all, don’t say it out loud! I can’t stress this enough. For your own health it is important that you remember this rule. Don’t ask someone about it. Don’t mention it to the pitcher’s proud father. Don’t even think about it. Just pretend it’s not happening and that there’s nothing special going on. If you hear someone less savvy than you, quickly silence them by any means possible, and inform them of this all-important rule. If you talk of the perfect game while it’s in progress you will jinx it and something will happen to ruin it. I am convinced that part of the reason there have only been 17 perfect games in the history of the Major Leagues is because there are too many people who don’t know this rule. Everyone on the field is knows it, and abides by it, but some drunk in the upperdeck who can’t keep his mouth shut ruins it and before you know it, the pitcher, who had been so perfect, loses his bid on an infield single or a “judy” just out of the reach of the second baseman. If we can work together and get this message out to everyone that sees a baseball game, I believe we can double the number of perfect games thrown in the Major Leagues in just five years. After all, if Kevin Costner can do it, why can’t Johan Santana or Roy Halladay?

Then again, maybe it’s good that perfect pitching is so rare. There are so many everyday achievements in baseball that are considered great or incredible, that the game needs something so unique, so incomparable, and so extraordinary that there’s only one word adequate to describe it—perfect.

The proceeds from the week long auction go to the Jimmy Fund organization to help fight cancer. It's a worthy cause if there ever was one, but I really can't believe it sold for that much money. First of all, it didn't really do anything. The Curse of the Bambino lasted for 86 years. Now that was a curse. This was just a poorly executed attempt. The Yankees didn't even play a single game in that new stadium. What's more, Ortiz started off the season ice cold, and has only now begun to produce. Maybe the curse backfired.

The proceeds from the week long auction go to the Jimmy Fund organization to help fight cancer. It's a worthy cause if there ever was one, but I really can't believe it sold for that much money. First of all, it didn't really do anything. The Curse of the Bambino lasted for 86 years. Now that was a curse. This was just a poorly executed attempt. The Yankees didn't even play a single game in that new stadium. What's more, Ortiz started off the season ice cold, and has only now begun to produce. Maybe the curse backfired.